این شناسایی با کمک تلسکوپ بایسپ۲(BICEP2) –

تصویربرداری پس زمینه قطبیت فراکهکشانی کیهان- در

قطب جنوب انجام شد. این محققان با همکاری

دانشمندان دانشگاه مینهسوتا، دانشگاه استنفورد،

موسسه فناوری کالیفرنیا و آزمایشگاه پیشرانش جت

ناسا پس از هفتهها کار که از رسانهای شدن آن

جلوگیری میکردند، هفته گذشته نتایج خود را در

مجله Physical Review Letters منتشر کردند. آنها

در چکیدهای اظهار کرده بودند که مدلشان هنوز

سوالات بزرگی را بیپاسخ نگهداشته است. به گفته

محققان، آنها غبار درون کهکشان راه شیری را که

ممکن است خوانشهای آنها را بیفایده نشان دهد،

حساب نکرده بودند. دو تحلیل مستقل اکنون نشان

میدهد که الگوهای در حال چرخش در قطبیت تابش

زمینه کیهانی ممکن است فقط غبار باشد.

اکنون دانشمندان به این نتیجه رسیدهاند که

دادههای کافی برای رد نظریه غبار وجود ندارد.

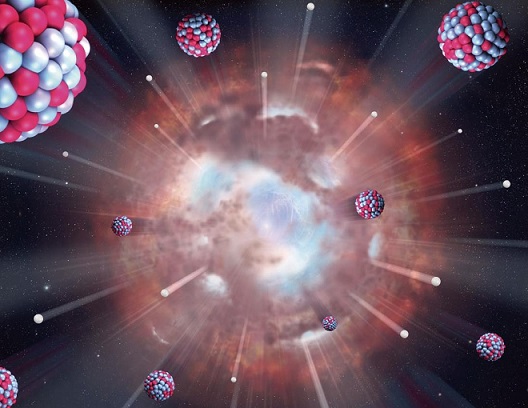

دانشمندان ابتدا با مشاهده زمینه ریزموج کیهانی یا

درخشش ضعیف به جای مانده از بیگ بنگ، اظهار کردند

که نوسانات کوچک به آنها سرنخهایی در مورد شرایط

جهان اولیه ارائه کرده است. به ادعای آنها، امواج

گرانشی درست لحظه ای پس از بیگ بنگ در سراسر جهان

به گردش درآمده بودند که در نهایت تلسکوپ بایسپ۲

موفق به کشف آنها شده بود. در هفتههای پس از این

ادعا، شماری از دانشمندان تردیدهایی را در مورد

یافتههای تیم بایسپ۲ اعلام کردند.

به گفته آلبرت اینشتین، زمانی که انفجار بزرگی

مانند بیگ بنگ رخ میدهد، ریزموجهایی را در

فضا-زمان بجا میگذارد که به امواج گرانشی معروف

هستند. اولین امواج گرانشی میتوانند به نمایش

اطلاعاتی در مورد تولد جهان بپردازد. دانشمندان

دریافتهاند که این موجها در زمان حرکت در فضا از

خود نشانههایی را در تابش زمینه کیهانی بجا

میگذارند. نظریه اینشتین نشان میدهد که این جهش

اولیه ممکن است جهان نوزاد را از چیزی بینهایت

کوچک به یک چیز به اندازه یک تیله تبدیل کرده

باشد. محققان مرکز فیزیک نجومی هاروارد اسمیتسونین

به ساخت آشکارسازهای تابش فوق حساس پرداخته و آنها

را در تلسکوپ رادیویی بایسپ۲ در قطب جنوب برای

شناسایی این ریزموجها قرار دادند. آنها سه سال به

اسکن حدود دو درصد آسمان پرداختند و پس از ۹ سال

این الگوهای چرخان را در تابش زمینه کیهانی ایجاد

شده شناسایی کردند که توسط امواج گرانشی بوجود

آمده در ابتدای جهان ایجاد شده بودند.

بسیاری از دانشمندان اکنون بر این باورند که یک

رشد ناگهانی ابتدایی و بسیار سریع رخ داده است اما

کشف این شواهد یک هدف کلیدی در پژوهش جهان بوده

است. این کشف به ارائه دریچه رو به جهان در ساعات

اولیه تولد آن پرداخته که بسیار کمتر از یک

تریلیونیوم ثانیه عمر داشته است. اگرچه این کار

باید توسط دانشمندان دیگر بازبینی شود اما هنوز

امکان اهدای جایزه نوبل به آن وجود دارد.

Astrophysicists are casting doubt on what

just recently was deemed a breakthrough in

confirming how the universe was born: the

observation of gravitational waves that

apparently rippled through space right after

the Big

Bang. If proven to be correctly

identified, these waves -- predicted in

Albert Einstein's theory of relativity --

would confirm the rapid and violent growth

spurt of the universe in the first fraction

of a second marking its existence, 13.8

billion years ago.

The

apparent first direct evidence of such

so-called cosmic inflation -- a theory that

the universe expanded by 100 trillion

trillion times in barely the blink of an eye

-- made with the help of a telescope called BICEP2,

stationed at the South Pole, was announced

in March by experts at theHarvard-Smithsonian

Center for Astrophysics. The telescope

targeted a specific area known as the

"Southern Hole" outside the galaxy where

there is little dust or extra galactic

material to interfere with what humans could

see.

"Detecting this signal is one of the most

important goals in cosmology today," John

Kovac, leader of the BICEP2 collaboration at

the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for

Astrophysics, said at the time. By observing

the cosmic microwave background, or a faint

glow left over from the Big Bang, the

scientists said small fluctuations gave them

new clues about the conditions in the early

universe.

The gravitational waves rippled through the

universe 380,000 years after the Big Bang,

and these images were captured by the

telescope, they claimed. If confirmed by

other experts, some said the work could be a

contender for the Nobel Prize.

But not everyone is convinced of the

findings, with skepticism surfacing recently

on blogs and scientific US journals such as

Science and New Scientist.

Paul Steinhardt, director of Princeton

University's Center

for Theoretical Science, addressed the issue

in the prestigious British journal Nature in

early June. "Serious flaws in the analysis

have been revealed that transform the sure

detection into no detection," Steinhardt

wrote, citing an independent analysis of the

BICEP2 findings.

That analysis was carried out by David

Spergel, a theoretical astrophysicist

who is also at Princeton. Spergel queried

whether what the BICEP2 telescope picked up

really came from the first moments of the

universe's existence. "What I think, it is

not certain whether polarized emissions come

from galactic dust or from the early

universe," he told AFP.

"We know that galactic dust emits polarized

radiations, we see that in many areas of the

sky, and what we pointed out in our paper is

that pattern they have seen is just as

consistent with the galactic dust radiations

as with gravitational waves."

When using just one frequency, as these

scientists did, it is impossible to

distinguish between gravitational waves and

galactic emissions, Spergel added.

The question will likely be settled in the

coming months when another, competing group,

working with the European Space Agency's Planck

telescope, publishes its results. The

Planck telescope observes a large part of

the sky -- versus the BICEP2's two percent

-- and carries out measurements in six

frequencies, according to Spergel.

"They should revise their claim," he said of

the BICEP2 team. "I think in retrospect,

they should have been more careful about

making a big announcement." He went on to

say that, contrary to normal procedure,

there was no external check of the data

before it was made public.

Philipp Mertsch of the Kavli

Institute for Particle Astrophysics and

Cosmology at

Stanford University said data from Planck

and another team should be able to "shed

more light on whether it is primordial

gravitational waves or dust in the Milky

Way. Let me stress, however, that what is

leaving me (and many of my colleagues)

unsatisfied with the state of affairs: If it

is polarized dust emission, where is it

coming from?" he said in an email to AFP.

Kovac, an associate professor of astronomy

and physics at Harvard, declined to respond

to requests for comment. Another member of

the team, Jamie Bock of the California

Institute of Technology, also declined to be

interviewed. At the time of their

announcement in March, the scientists said

they spent three years analyzing their data

to rule out any errors.