Fierce debate rages around entrepreneur Thane Heins' dogged

pursuit of green engine

Tyler Hamilton

ENERGY REPORTER

Thane Heins, tired and a little grumpy after a long flight from

California, walks onto the stage of an Ottawa conference room

and begins a sales pitch that usually raises more eyebrows than

money.

One of three entrepreneurs chosen earlier this month to present

at a “Pitch The Dragons” contest, a spin on the CBC show Dragons’

Den, Heins has invented a technology that he says will put

out more energy than it consumes. His invention, he boldly

claims, offers a way to make electric cars that can travel

hundreds of kilometres from the energy in a small, inexpensive

battery.

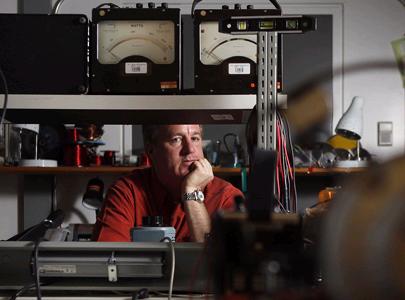

CHRISTOPHER PIKE/FOR THE TORONTO STAR

Ottawa inventor Thane Heins is steadily winning supporters

for his electrical motor, which he claims can produce more

energy than it consumes. While many are skeptical of the

theory, no one has been able to disprove it. (Feb. 12, 2009)

It’s a tough crowd. One of the contest judges is TV-show judge

Robert Herjavec, a multimillionaire who just minutes earlier

shared with the audience his own story of success and the life

it now funds - the fancy gas-guzzling cars, the mansion, the

luxurious yacht.

The two men are oil and water. Heins, who wants to help the

world kick its fossil-fuel addiction, immediately gets his back

up. Herjavec is dismissive from the get-go.

“It turned into a shouting match in front of 300 people,” Heins

says later that day. “I didn’t mind him kicking sand in my face,

but the thing that really got me is when he said I don’t get it.

He pushed me a little too far and I fought back.”

It was just another day for this underdog entrepreneur, a man

trying to convince mainstream society he has discovered

something real, which in this case means it has broken a major

law of physics.

The Star first

profiled Heins and his controversial invention a year ago. In a

nutshell, he had figured out a way to eliminate the

electromagnetic friction that typically limits the performance

of an electrical generator – an effect known as “Back EMF.” Not

only that, but he also learned how to redirect that magnetic

energy so that, instead of causing resistance, it gave an

electrical motor connected to the generator a significant boost.

The result, as far as Heins was concerned, violated Lenz’s law

or what’s often called the law of diminishing returns. For many,

that equates to a perpetual motion machine, an impossible claim

in the conventional field of physics.

Within no time the story spread globally across the Internet,

became chatter on blogs, and triggered a flood of email to this

reporter’s inbox – some praising Heins for his determination,

others calling the Star irresponsible for giving credibility to

his claim. The story, love it or hate it, was the second-most

read article on TheStar.com in

2008.

Much has happened over the past 12 months. Heins still operates

out of a lab out at the University of Ottawa, he continues to

evolve his invention, and he routinely demonstrates those

improvements to the world by posting videos on YouTube.

“The last video I watched still showed evidence of some

fundamental misunderstandings of physics, combined with wishful

thinking,” said Seanna Watson, an electrical engineer who is

also a member of a scientific group called Ottawa Skeptics.

Heins gave the group a demonstration of his technology shortly

at the Star’s story was published. Two months later Watson

posted a critique online titled “In This Town We Obey The Law of

Thermodynamics.” Yes, she admitted, the electrical motor does

speed up without any increase in input power, but increased

speed does not automatically mean an increase in mechanical

work.

“Heins appears earnest and basically honest, but persistently

self-deluded,” Watson wrote. “While the speed-up behaviour of

the generator currently lacks an established explanation, there

is no reason to think that it represents any challenge to

currently known laws of physics.”

It’s a criticism Heins has heard before: You haven’t proved

you’re right, so you must be wrong. At the same time, nobody has

been able to prove he’s wrong.

Some want to believe, or have kept an inquiring mind. Heins has

been contacted by NASA, he’s had several investors,

entrepreneurs, engineers and academics show up at his lab for a

demonstration. Heins always obliges -- he says he has nothing to

hide.

At one point last spring, rock legend Neil Young wanted to adapt

Heins’ invention to power a 1959 Lincoln Continental MK IV,

which is being entered into the $10-million automotive X-Prize –

a contest in search of the world’s most efficient automobile.

Heins, Young, and his engineer Uli Kruger had much dialogue over

email and telephone about the rock star’s “LincVolt” project. At

one point, Heins sent Young some information by email on the

performance of his generator and copied the message to dozens of

other people unrelated to Young’s project.

Young replied to Heins that he didn’t appreciate his private

email being broadcast to the world. “Please do not do this

again!” he wrote, but then quickly breezed over the incident.

“This in no way negates my enthusiasm and curiosity about your

project,” he assured Heins.

Heins, not one to worship the famous, sent a terse response: “I

just sent you an email with proof that my generator violates the

Law of Conservation of Energy and you are worried about your

private email? Are you serious?” He accused Toronto-born Young

of being shallow.

The relationship eventually fizzled. Two week after that

exchange, Young, in an email to the Star,

was still gracious in his assessment of Heins’ invention. “I am

impressed… it is on our list of things to watch.”

Day by day, bit by bit, Heins’ passion and persistence is

steadily gaining him supporters – people convinced that what

they’re seeing is important enough to move the technology out of

the lab and into real-world applications.

Through his Ottawa-based company Potential Difference Inc.,

Heins has been in serious talks with a designer of small wind

turbines in Montreal, a senior engineer from a large utility in

Turkey, and a small manufacturer of electrical equipment in

Toronto. He’s altered the design of his prototype as well by

developing a high-voltage “self-excited” motor coil.

“We can use it to accelerate (the motor shaft) from 100

revolutions per minute to 3,500 without adding an ounce of

power,” according to Heins.

His most promising partnership so far is with California Diesel

& Power, a $10-million company that sells back-up generators for

cellphone towers throughout California. AT&T is one of its