|

‘They’ll find the God particle by

summer.’ And Peter Higgs should know

Published on Saturday

25 February 2012

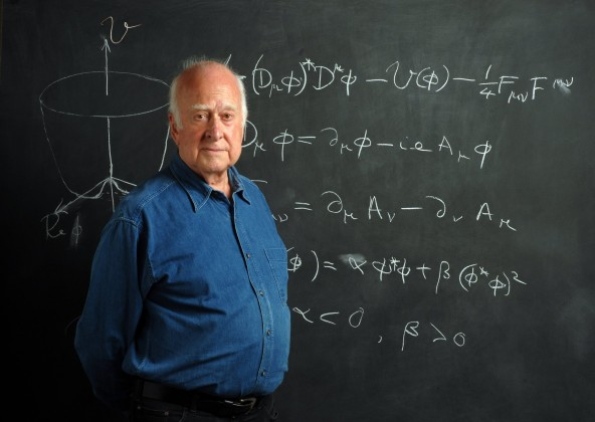

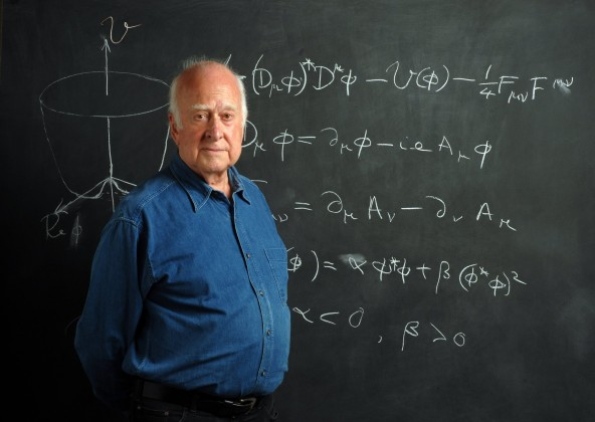

Peter Higgs, pictured at Edinburgh University

Renowned physicist Professor Peter Higgs gives a

rare interview to Jenny Fyall as he receives the

Edinburgh Award

THE fabled Higgs boson that will help

explain the origins of the universe will be found

this summer, the scientist who gave his name to the

particle has predicted.

Professor Peter Higgs told The

Scotsman he thought scientists at Cern working with

the Large Hadron Collider would find evidence that

the elusive particle exists within a matter of

months.

The acclaimed 82-year-old theoretical

physicist came up with the now famous theory in 1964

which provides an explanation for the origins of

mass as a property of matter.

However, almost half a century later,

the Higgs boson that is a fundamental part of the

theory has still not been found.

“It’s found well enough to satisfy

quite a few people but not well enough to satisfy

the standards of Cern,” the professor said.

“The kind of certainty they want is

where it becomes a few million to one against it

being any other stray effect which might simulate

it.

“It should be settled during the

summer.”

He added: “To me it looks extremely

promising at the moment but the experimentalists

want it more cut and dried than it is at the

moment.”

Prof Higgs was speaking ahead of a

ceremony last night to present him with the

prestigious Edinburgh Award for his contribution to

the city.

When the Higgs boson, which has

become known as the God Particle, is confirmed to

exist, he said he would celebrate by opening a

bottle of champagne.

Asked whether he was excited by the

revelations in December last year that data from the

Large Hadron Collider had provided the greatest

hints yet that the Higgs boson may exist, he said:

“From time to time yes. This is something I have

lived with for a long time now. It is nearly 48

years since I did this work in 1964.”

However, Prof Higgs, who does not own

a television, said he did not keep very closely up

to date with latest developments at Cern, relying

instead on his former colleagues to fill him in.

He had not heard the news, reported

on Thursday, that an explanation had been found for

the results of recent experiments at Cern that

seemed to show particles called neutrinos travelling

faster than the speed of light. It turned out a

loose cable could have been responsible.

He said: “That’s a relief. It looked

so surely like some sort of mistake but nobody knew

where the mistake was.”

If the Higgs boson is confirmed to

exist, Prof Higgs has been widely tipped to be in

line for a Nobel Prize.

“I find it hard to imagine but it’s

not recent news to me that it’s a possibility,” he

said.

Asked how he deals with the attention

of being linked to the Higgs boson, the Emeritus

Professor at the University of Edinburgh, who rarely

gives interviews, said: “Since I’m getting older I

find it an advantage that it takes me some time to

walk to where my telephone is.”

And he suggested during yesterday’s

interview that he thought it was unfair that his

name alone had become linked to the particle.

Several other scientists came up with similar

theories at the same time.

He described how his name had been

“plastered all over everything to do with the

theory” and that this “neglected to give credit to

the other people involved”. He added: “A lot of

people have been involved in this in various ways.

When it comes to publicity I think the publicity

gets a bit biased sometimes.”

He revealed that rather than coming

to him during a flash of inspiration during a walk

in the Cairngorms in 1964, as commonly reported, the

theory had actually been formulated in Edinburgh.

“It was probably somewhere in

Edinburgh during a weekend in July,” he said. “It

wasn’t a sort of eureka moment. It was a gradual

realisation.”

Prof Higgs, who was born near

Newcastle but settled in Edinburgh after falling in

love with the city when he visited as a student,

revealed to The Scotsman yesterday that by carrying

out research into his family tree he had discovered

that both his grandfather, James Coghill, and

great-grandfather had also lived in the capital.

It turned out his great-grandfather,

who was born in Caithness in 1805, was a spirit

merchant on the Royal Mile next to what is now

Deacon Brodie’s Tavern.

“I rather fell for the city the first

time I saw it lit up at night,” he said. “There’s no

other city in the UK like it.

He said he was “very pleased” to have

been honoured with the Edinburgh Award.

“Edinburgh is my adopted home. It’s a

place where I wanted to come and live and I managed

to arrange my life so it happened.”

The physicist, who has two sons and

two grandchildren who all live in Edinburgh, added

that getting the award had cemented his feeling that

he was now “part of the Edinburgh scene”, which he

said had first been hinted to him when he discovered

he featured in one of Alexander McCall Smith’s 44

Scotland Street novels. Prof Higgs is the fifth

person to receive the Edinburgh Award, which is

given to people who have made an outstanding

contribution to the city.

He was presented with the Loving Cup

at a ceremony last night and his handprints have

been engraved in the stone in the City Chambers’

quadrangle.

The Rt Hon George Grubb, Lord

Lieutenant and Lord Provost of the City of

Edinburgh, said: “His proposal of what has now

become known as the Higgs boson has not only

significantly advanced our knowledge of particle

physics, culminating in the Standard Model, but has

also given him a huge international reputation.

“Professor Higgs’ work with the

University of Edinburgh has put this city on an

international stage and as such he is undoubtedly a

most deserved recipient of one of Edinburgh’s most

prestigious civic awards.”

And Alan Walker, honorary fellow of

the University of Edinburgh and a member of the

Particle Physics Experiment Group said: “This award

is richly deserved, not only for the work that has

led to worldwide acclaim, but for his inspiration of

students, many of whom have gone on to do great

things. Indeed, some are currently involved in the

searches at the ATLAS detector for the Higgs boson.

“This is indeed a very proud day for

both the university and the City of Edinburgh.”

The theory: Mass – and why it just

disappears

Published on Saturday

25 February 2012

HIGGS became interested in what must

be one of the most curious puzzles in physics: why

the objects around us weigh anything.

Until recently, few even questioned

where mass comes from.

Isaac Newton coined the term in 1687

in his famous tome, Principia Mathematica, and for

200 years scientists were happy to think of mass as

simply existing.

Some objects had more mass than

others – a brick versus a book, say – and that was

that. But scientists now know the world is not so

simple. While a brick weighs as much as the atoms

inside it, according to the best theory physicists

have – one that has passed decades of tests with

flying colours – the basic building blocks inside

atoms weigh nothing at all. As matter is broken down

to ever smaller constituents, from molecules to

atoms to quarks, mass appears to evaporate before

our eyes.

Higgs came up with an elegant

mechanism to solve the problem. It showed that at

the very beginning of the universe, the smallest

building blocks of nature were truly weightless, but

became heavy a fraction of a second later, when the

fireball of the big bang cooled. His theory was a

breakthrough in itself, but something more profound

dropped out of his calculations.

Higgs’s theory showed that mass was

produced by a new type of field that clings to

particles wherever they are, dragging on them and

making the heavy. Some particles find the field more

sticky than others. Particles of light are oblivious

to it. Others have to wade through it like an

elephant in tar. So, in theory, particles can weigh

nothing, but as soon as they are in the field, they

get heavy.

Detecting the field itself is thought

to be impossible with modern technology, but Higgs

also predicted a particle that is created in the

field, and finding this would be the proof they

sought.

Officially, the particle is called

the Higgs boson, but its elusive nature and

fundamental role led a prominent scientist to rename

it the God particle.

• Extract

from Massive: The Hunt for the God Particle by Ian

Sample

Peter Higgs: Lecturer who fell in

love with Scotland

Published on Saturday

25 February 2012

PETER Ware Higgs, now 82, was born in

Wallsend, North Tyneside in May 1929.

He became enthralled as a schoolboy

by Paul Dirac, Britain’s unsung hero of theoretical

physics.

As a child he received some of his

early schooling at home, partly due to his father’s

job as a sound engineer for the BBC, which meant the

family moved around a lot.

He graduated with a first-class

honours degree in physics from King’s College

London, as well as a masters and PhD.

In 1960 he took up a lecturing post

at the University of Edinburgh, a city he had fallen

in love with after he hitch-hiked to Scotland to go

walking in the Highlands as a student.

Four years later, Prof Higgs carried

out the work that has made him famous in the world

of physics and resulted in his portrait hanging in

the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

At that time, no-one realised his

research was important and in fact, the second paper

he wrote about it was rejected as irrelevant by

Europe’s leading journal for particle physics and he

had to send it to a rival American journal, Physical

Review Letters.

Two other scientists, Robert Brout

and Francois Englert at the Free University of

Brussels, came to the same conclusions at a similar

time and it is said Prof Higgs can feel embarrassed

that the particle bears his name. On occasion he has

instead referred to it as the “boson named after

me”.

He retired in 1996 and is now

Emeritus Professor at the University of Edinburgh.

He has two sons, Chris, a computer

scientist, and Jonny, a jazz musician, and two

grandchildren.

He has no television but spends his

time walking in the Highlands, playing with his

grandchildren, reading novels and enjoying classical

music.

Confirmation of his place in

Edinburgh society was established with a mention in

Alexander McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street novels

The pioneer has already been awarded

the Wolf Prize – considered to be the second most

important prize in physics – but he refused to fly

to Jerusalem to receive the award, because he is

opposed to Israel’s actions in the Middle East.

The greatest prize is now in his

sights. If the hunt for the God particle is

successful, he is widely expected to be awarded the

Nobel Prize.

Source: scotsman

|