C reative

Particle

Higgs

CPH Theory is based on Generalized light velocity from energy into mass.

CPH Theory in Journals

|

We May Not Be Alone…

|

|

Could multiple universes theory reshape science—and faith?02.21.2012

“Science’s crisis of faith.” That’s how Harper’s magazine headlined an article last December describing a revolutionary theory that could not only upend physics, but blur the border between science and religion. Some BU physicists dispute that last point, made by MIT physicist Alan Lightman in his piece. One, Nobel physics laureate Sheldon Glashow, BU’s Arthur G. B. Metcalf Professor of Mathematics and Science, doesn’t buy the theory itself, which holds that physicists’ search for fundamental laws governing, well, everything in the universe, has been a colossal waste of time. In fact, argues the new view, there are many universes with different traits, dictated by different parameters than those in our own universe. “Some of the most basic features of our particular universe are indeed mereaccidents—a random throw of the cosmic dice,” Lightman writes of the implications of this “multiverse” theory. “In which case, there is no hope of ever explaining our universe’s features in terms of fundamental causes and principles.” According to the theory, the just-right parameters that allowed us and all life to emerge was our dumb luck; in another universe, those parameters may not exist, and so neither does life. Still other universes may require different parameters to support life. (The fact that our parameters are so finely tuned has led some people to embrace intelligent design, which most scientists reject, Lightman notes.) This new paradigm would be upsetting enough by itself, which may be why multiple universes hitherto have been the stuff of science fiction, like Star Trek(remember the alternate-universe Mr. Spock with a beard?) or Lost in Space. (Fortunately for those shows’ characters, they always managed to beam into another universe that supported life.) But Lightman adds a match to the fire: “We have no conceivable way of observing these other universes and cannot prove their existence. Thus, to explain what we see in the world and in our mental deductions, we must believe in what we cannot prove. Sound familiar? Theologians are accustomed to taking some beliefs on faith. Scientists are not.”

Photo by Kalman Zabarsky Discussions of the multiverse proceed so insanely arcanely, writes Lightman, that “it is perhaps impossible to say how far apart the different universes may be, or whether they exist simultaneously in time.” Nonetheless, says Martin Schmaltz (left), a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of physics, the theory “may well be right and deserves to be considered.” But he agrees that we’ll never observe other universes, so there are “no direct, observable predictions” flowing from the theory. “The hope is that there might be indirect predictions” about phenomena facilitated by the multiverse idea. If the multiverse turns out to be useless in explaining data and making predictions, Schmaltz says, “the question of whether there are other universes would indeed merely become a question of faith, which I am not much interested in.” Glashow has reached that point. (Schmaltz enjoyed the Harper’s piece. Glashow (below), asked if he read it: “Nah.”) “The multiverse is more a notion than a theory,” he says dismissively, describing the concept as “an abject surrender,” because it can’t be tested. As to whether the new theory poses a crisis of faith, he says, “Only to its believers.”

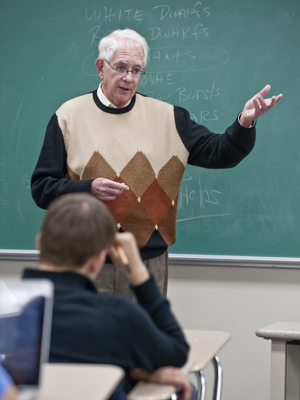

Photo by Vernon Doucette Alan Marscher a CAS professor of astronomy, discusses the multiverse in a course he teachers for non–astronomy majors and considers it a possible explanation of our universe’s characteristics. Still, he says, “it is based on an extrapolation of quantum physics, and extrapolations tend to be dangerous.” Lightman argues, for example, that the 1998 discovery of dark energy, the force believed to be making the universe expand ever faster, “practically demands” the multiverse to explain it. Marscher disagrees, saying dark energy’s origins remain a mystery and that the multiverse is just one possible explanation. We’ll never talk with any beings in any other universe, according to the theory—to steal an amusing analogy from Stephen Colbert, it seems the multiverse is like a city bus. “Followers of the multiverse have no conceivable way of observing these other universes and cannot prove their existence,” Glashow says. “Their approach seems to me more like medieval theology than science.” Marscher dubs the multiverse “atheistic theology…an unthinking creator.” “If someone were to devise an observational test of it, then it could be called a scientific hypothesis,” he says. “So it represents a theology that some scientists hope to convert into a scientific model. I see nothing wrong with that, as long as the fact that it’s scientists who are proposing it doesn’t confuse people into thinking that it’s a valid scientific theory.” According to Lightman, some leading theoretical physicists (he cites MIT colleagueAlan Guth and the Steven Weinberg of the University of Texas) “reluctantly” buy the multiverse theory as the best explanation for the exquisitely precise calibration of natural forces in our universe that allowed life to emerge: if there are many universes, one is bound to have our life-supporting parameters, while others will be “dead, lifeless hulks of matter and energy,” Lightman writes. In short, we got lucky.

Source: BU Today

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Newest articles

|

|

Sub quantum space and interactions from photon to fermions and bosons |

Interesting articles

Since 1962 I doubted on Newton's laws. I did not accept the infinitive speed and I found un-vivid the laws of gravity and time.

I learned the Einstein's Relativity, thus I found some answers for my questions. But, I had another doubt of Infinitive Mass-Energy. And I wanted to know why light has stable speed?