|

PASADENA, Calif. – In the first

comprehensive satellite study of its kind, a

University of Colorado at Boulder-led team used NASA

data to calculate how much Earth's melting land ice

is adding to global sea level rise.

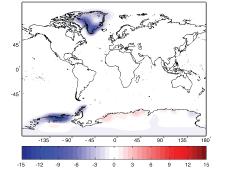

Using satellite measurements from the

NASA/German Aerospace Center Gravity Recovery and

Climate Experiment (GRACE), the researchers measured

ice loss in all of Earth's land ice between 2003 and

2010, with particular emphasis on glaciers and ice

caps outside of Greenland and Antarctica.

The total global ice mass lost from

Greenland, Antarctica and Earth's glaciers and ice

caps during the study period was about 4.3 trillion

tons (1,000 cubic miles), adding about 0.5 inches

(12 millimeters) to global sea level. That's enough

ice to cover the United States 1.5 feet (0.5 meters)

deep.

"Earth is losing a huge amount of ice

to the ocean annually, and these new results will

help us answer important questions in terms of both

sea rise and how the planet's cold regions are

responding to global change," said University of

Colorado Boulder physics professor John Wahr, who

helped lead the study. "The strength of GRACE is it

sees all the mass in the system, even though its

resolution is not high enough to allow us to

determine separate contributions from each

individual glacier."

About a quarter of the average annual

ice loss came from glaciers and ice caps outside of

Greenland and Antarctica (roughly 148 billion tons,

or 39 cubic miles). Ice loss from Greenland and

Antarctica and their peripheral ice caps and

glaciers averaged 385 billion tons (100 cubic miles)

a year. Results of the study will be published

online Feb. 8 in the journal Nature.

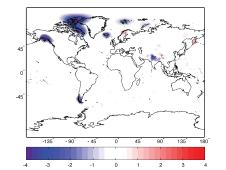

Traditional estimates of Earth's ice

caps and glaciers have been made using ground

measurements from relatively few glaciers to infer

what all the world's unmonitored glaciers were

doing. Only a few hundred of the roughly 200,000

glaciers worldwide have been monitored for longer

than a decade.

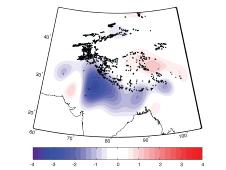

One unexpected study result from

GRACE was that the estimated ice loss from high

Asian mountain ranges like the Himalaya, the Pamir

and the Tien Shan was only about 4 billion tons of

ice annually. Some previous ground-based estimates

of ice loss in these high Asian mountains have

ranged up to 50 billion tons annually.

"The GRACE results in this region

really were a surprise," said Wahr, who is also a

fellow at the University of Colorado-headquartered

Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental

Sciences. "One possible explanation is that previous

estimates were based on measurements taken primarily

from some of the lower, more accessible glaciers in

Asia and extrapolated to infer the behavior of

higher glaciers. But unlike the lower glaciers, most

of the high glaciers are located in very cold

environments and require greater amounts of

atmospheric warming before local temperatures rise

enough to cause significant melting. This makes it

difficult to use low-elevation, ground-based

measurements to estimate results from the entire

system."

"This study finds that the world's

small glaciers and ice caps in places like Alaska,

South America and the Himalayas contribute about

0.02 inches per year to sea level rise," said Tom

Wagner, cryosphere program scientist at NASA

Headquarters in Washington. "While this is lower

than previous estimates, it confirms that ice is

being lost from around the globe, with just a few

areas in precarious balance. The results sharpen our

view of land-ice melting, which poses the biggest,

most threatening factor in future sea level rise."

The twin GRACE satellites track

changes in Earth's gravity field by noting minute

changes in gravitational pull caused by regional

variations in Earth's mass, which for periods of

months to years is typically because of movements of

water on Earth's surface. It does this by measuring

changes in the distance between its two identical

spacecraft to one-hundredth the width of a human

hair.

The GRACE spacecraft, developed by

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.,

and launched in 2002, are in the same orbit

approximately 137 miles (220 kilometers) apart. The

California Institute of Technology manages JPL for

NASA.

For more on GRACE, visit:

http://www.csr.utexas.edu/grace and http://grace.jpl.nasa.gov .

For more information about NASA and

agency programs, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov .

JPL is managed for NASA by the

California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Additional media contact: Jim Scott,

CU-Boulder, 303-492-3114,

jim.scott@colorado.edu .

Alan Buis 818-354-0474

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

Alan.buis@jpl.nasa.gov

Steve Cole 202-358-0918

NASA Headquarters, Washington

Stephen.e.cole@nasa.gov

Source: Nasa |