|

Leading physicist John Wheeler dies at age 96

April

14, 2008

by

Kitta MacPherson

John Archibald Wheeler, a legend in physics who

coined the term "black hole" and whose myriad scientific

contributions figured in many of the research advances of the

20th century, has died.

Wheeler, the Joseph Henry Professor of Physics Emeritus at

Princeton University, was 96. He succumbed to pneumonia on

Sunday, April 13, at his home in Hightstown, N.J.

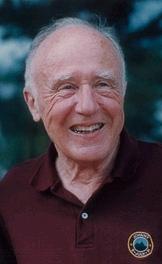

John Wheeler in 1991

Over a long, productive scientific life, he was

known for his drive to address big, overarching questions in

physics, subjects which he liked to say merged with

philosophical questions about the origin of matter, information

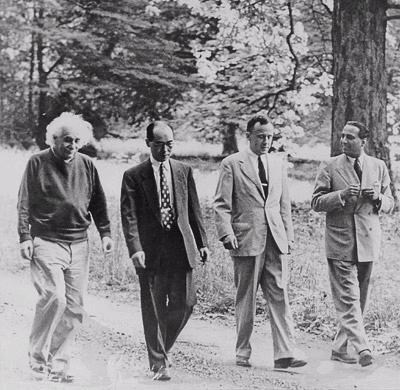

and the universe. He was a young contemporary of Albert Einstein

and Niels Bohr, was a driving force in the development of both

the atomic and hydrogen bombs and, in later years, became the

father of modern general relativity.

"Johnny Wheeler probed far beyond the frontiers of human

knowledge, asking questions that later generations of physicists

would take up and solve," said Kip Thorne, the Feynman Professor

of Theoretical Physics at the California Institute of

Technology, a prolific researcher and one of Wheeler's

best-known students. "And he was the most influential mentor of

young scientists whom I have known."

Wheeler, according to James Peebles, Princeton's Albert Einstein

Professor of Science Emeritus, was "something approaching a

wonder of nature in the world of physics."

Throughout his lengthy career as a working scientist -- he

maintained an office in Jadwin Hall until 2006 -- he concerned

himself with what he termed "deep, happy mysteries." These were

the laws of nature on which all else is built.

He also helped launch the careers of many prominent modern

theoretical physicists, among them the late Nobel laureate

Richard Feynman. He learned best by teaching. Universities have

students, he often said, to teach the professors.

"Johnny," which is what he was called by everyone, including his

children, was born in Jacksonville, Fla., on July 9, 1911, the

first of four children, to Joseph and Mabel ("Archie") Wheeler,

a librarian and a homemaker, respectively. The family moved when

Joseph changed jobs, which happened frequently. Over the years,

they lived in Florida, California, Ohio, Washington, D.C.,

Maryland and Vermont. Wheeler discovered science through his

father, who brought books home for the family to read to help

him judge whether they were worth purchasing for the library.

Wheeler devoured Sir John Arthur Thomson's classic "Introduction

to Science" and Franklin Jones' "Mechanisms and Mechanical

Movements." He was guided by the second book to build a

combination lock, a repeating pistol and an adding machine --

all from wood. He built crystal radio sets and strung telegraph

wires between his home and his best friend's. He almost blew off

one hand with dynamite one morning, tinkering with material that

had been declared off-limits.

Wheeler was the first in his family to become a scientist,

heading to Johns Hopkins University on a scholarship when he

was 16, and finishing in 1933, at age 21, with a doctoral

degree in physics. He went on to work at the University of

Copenhagen with the eminent physicist Niels Bohr, with whom

he co-wrote the original paper on the mechanism of nuclear

fission that helped lead to the development of the atomic

bomb. After World War II, Wheeler joined the Los Alamos

Scientific Laboratory Project for a year, playing a central

role in developing the hydrogen bomb and serving as a mentor

to the physicist Richard Feynman.

He served as a member of the Princeton faculty from 1938

until his retirement in 1976, after which he served as

director of the Center for Theoretical Physics at the

University of Texas-Austin until 1986.

"Throughout his life, Johnny was an extraordinarily

productive theoretical physicist," said Marvin "Murph"

Goldberger, the president emeritus of Caltech, who had an

office near Wheeler for decades as a longtime Princeton

faculty member. "His work was categorized by great

imagination and great thoroughness."

Looking back over his own career, Wheeler divided it into

three parts. Until the 1950s, a phase he called "Everything

Is Particles," he was looking for ways to build all basic

entities, such as neutrons and protons, out of the lightest,

most fundamental particles. The second part, which he termed

"Everything Is Fields," was when he viewed the world as one

made out of fields in which particles were mere

manifestations of electrical, magnetic and gravitational

fields and space-time itself. More recently, in a period he

viewed as "Everything Is Information," he focused on the

idea that logic and information is the bedrock of physical

theory.

"John Wheeler, who started life with Niels Bohr in the '30s,

in the nuclear physics era, became the father figure of

modern general relativity two decades later," said Stanley

Deser, a general relativitist at Brandeis University.

"Wheeler's impact is hard to overstate, but his insistence

on understanding the physics of black holes is one shining

example."

Described by colleagues as ever ebullient and optimistic,

Wheeler was known for sauntering into colleagues' office

with a twinkle in his eye, saying, "What's new?" He gave

high-energy lectures, writing rapidly on chalkboards with

both hands, twirling to make eye contact with his students.

He entered physics in the 1930s by applying the new quantum

mechanics to the study of atoms and radiation. Within a few

years, he turned to nuclear physics because it seemed to

hold the promise of revealing new and deeper laws of the

microscopic world. But it was "messy," he would later write,

and resistant to answers. Besides, working on fission, so

crucial to national defense during World War II, was a job,

not a calling, he said.

In his autobiography, titled "Geons, Black Holes and Quantum

Foam," written with his former student, the physicist

Kenneth Ford, Wheeler found "the love of the second half of

my life" -- general relativity and gravitation -- in the

post-war years. "When they emerged, I finally had a

calling," he said.

He liked to name things.

In the fall of 1967, he was invited to give a talk on

pulsars, then-mysterious deep-space objects, at NASA's

Goddard Institute of Space Studies in New York. As he spoke,

he argued that something strange might be at the center,

what he called a gravitationally completely collapsed

object. But such a phrase was a mouthful, he said, wishing

aloud for a better name. "How about black hole?" someone

shouted from the audience.

That was it. "I had been searching for just the right term

for months, mulling it over in bed, in the bathtub, in my

car, wherever I had quiet moments," he later said. "Suddenly

this name seemed exactly right." He kept using the term, in

lectures and on papers, and it stuck.

He also came up with some other monikers, perhaps less well

known outside the world of physics. A "geon," which he said

probably doesn't exist in nature but helped him think

through some of his ideas, is a gravitating body made up

entirely of electromagnetic fields. And "quantum foam,"

which he said he found himself forced to invent, is made up

not merely of particles popping into and out of existence

without limit, but of space-time itself, churned into a

lather of distorted geometry.

Despite his sunny disposition, he carried with him a secret

sadness. "He was devoted to the memory of his younger

brother, Joe, a Ph.D. in American history with wife and

child, who was killed in the bitter fighting against the

Germans in northern Italy," said Letitia Wheeler Ufford, his

oldest child. "His brother's last words to him were 'Hurry

up, John,' as he sensed that his older brother was working

on weaponry to end the war. As he got older, our father wept

often over this brother."

And he had a brush with controversy, though he ultimately

redeemed himself. In January 1953, while traveling on a

sleeper car to Washington, D.C., he lost track of a

classified paper on the hydrogen bomb which had been in his

briefcase. It was there when he went to bed but was missing

by morning. He was personally reprimanded by military

officials at the insistence of President Eisenhower and, as

a strong believer in national defense was personally

embarrassed by the incident. Years later, in December 1968,

he was presented with the Fermi Award by President Johnson

for his contributions to national defense as well as to pure

science. "I felt forgiven," he wrote.

What drove Wheeler so ferociously for so many decades may be

best expressed by the physicist himself. In his

autobiography, he put it this way: "I like to say, when

asked why I pursue science, that it is to satisfy my

curiosity, that I am by nature a searcher, trying to

understand. Now, in my 80s, I am still searching. Yet I know

that the pursuit of science is more than the pursuit of

understanding. It is driven by the creative urge, the urge

to construct a vision, a map, a picture of the world that

gives the world a little more beauty and coherence than it

had before. Somewhere in the child that urge is born."

Wheeler was pre-deceased by his wife, Janette Hegner

Wheeler, who died last October. He is survived by his three

children: Letitia Wheeler Ufford of Princeton; James English

Wheeler of Ardmore, Pa.; and Alison Wheeler Lahnston of

Princeton. He is also survived by eight grandchildren, six

step-grandchildren, 16 great-grandchildren and 11

step-great-grandchildren.

Burial will be private at his family's gravesite in Benson,

Vt. There will be a memorial service at 10 a.m. Monday, May

12, at the Princeton University Chapel. The family asks that

gifts be made to Princeton

University, the University of Texas-Austin for the John

Archibald Wheeler Graduate Fellowship or to Johns Hopkins

University.

Source

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Newest

articles

|